We are now at the halfway point in this Lenten cinema series. Jésus de Montréal is movie number four, and we have four more to go after this. While I have enjoyed each of the three previous films in different ways, this one is my favorite thus far. The story and execution are just so unusual and unique with a mixture of earthiness and mysticism wrapped up in a type of non-religious Christianity. If that even makes sense. That’s why this is The Avant-Garde Jesus Movie. Leave it to the French — or the Québécois in this case — to experiment with presenting such an ancient, well-known story in a completely unexpected way.

Jésus de Montréal follows Daniel Coulombe, a talented, unknown actor, who is hired by the priest of a Roman Catholic pilgrimage site in Montreal to update and modernize their small Passion play production. We get to see a bit of the original version on VHS, and it’s basically an extremely traditional and overly theatrical Stations of the Cross. Daniel conducts background research — mostly archaeological and historical — to bring different perspectives to such a well-known story, gathers a diverse troupe of actors, and finally stages the modernized Passion play in the gardens of the pilgrimage site. As the film continues to unfold, the trajectories of the characters in the Gospels begin to merge with the actors who are portraying them.

The film is filled with allusions to the New Testament and even other portions of the Bible that are simply delightful when you realize what is being referenced in sometimes thoroughly unexpected ways.

Daniel gathers a small group of actors from a variety of backgrounds: allusion to Jesus recruiting former tax collectors, zealots, and fishermen to work together.

Daniel and Constance find Martin in a recording studio where he and two actresses are busy at work dubbing the French audio version of a porno: allusion to Jesus being a friend of prostitutes and sinners.

Daniel, Constance, and Martin find René in a studio where he’s recording the voiceover for a science documentary which covers the Big Bang and formation of the universe: allusion to Genesis 1 and the story of Creation but from a purely scientific perspective.

Daniel and Mireille both separately move in with Constance since (for different reasons) they have nowhere else to go: allusion to Jesus having no permanent home and the congregation of a community of outcasts.

While Daniel is having a bath in a sort of open bathroom space, Mireille casually helps wash his chest and shoulders: allusion to the woman anointing Jesus’ feet with perfume and/or Mary of Bethany anointing Jesus with oil.

Daniel goes with Mireille to an audition where she is sexually harassed and humiliated by the casting directors. He confronts them, flips over their tables, destroys their TV and camera, and chases them out of the building with a whip made from cables: allusion to Jesus driving out the moneylenders in the Jerusalem Temple.

Daniel refuses to defend himself in court from the ensuing charges of destruction of property, assault, etc.: allusion to Jesus’ trials before Pilate where he doesn’t defend himself either.

A lawyer — with his 17-year-old arm candy — stroll with Daniel through the halls of a skyscraper discussing fame, fortune, power, and how he can have it all: allusion to the Temptation in the Wilderness.

The Catholic priest and higher-ups in the Church are angry about the liberties being taken in this modernized Passion play all while the spectators absolutely love it: allusion to Jesus being at odds with the religious authorities while extremely popular with the general public.

During one of the performances, Daniel directs the ire of the Seven Woes monologue to a small group of priests in attendance who are clearly annoyed with the script: allusion to Jesus’ Seven Woes being originally directed at the temple priests.

These are just the broad strokes leading up to the finale. The film is chock-full of allusions, allegories, and metaphors based on daring and innovative interpretations of the Gospels. But the most profound of them all comes in the last 10–15 minutes with an inventive rendition of the death and resurrection of Christ. But we’ll get to that in a bit.

There are two fantastic interactions with a certain earnest librarian in the film that I have to mention. The first occurs when Daniel is busy with his research in the library and she approaches him with a cart of the books he had requested, ostensibly all about Jesus.

“Est-ce que vous cherchez Jésus?” she asks. (Are you looking for Jesus?)

“Oui.”

She sets the books down on the table in a rather softly dramatic way and then makes some kind of meaningful eye contact with him.

“C’est lui qui va vous trouver.” (It’s him who is going to find you.)

There’s a brief silence that Daniel breaks with an awkward, “Ah, oui.”

Unsolicited advice/guidance from an overly enthusiastic religious devotee is something I can definitely relate to. But it gets even better.

In the second scene where the librarian appears, she has just attended one of the performances with her (probable) husband, and they are having a conversation with two of the other actors, René and Martin. As it turns out, she is a total End Times conspiracy theorist religious nutter who manages to mention 666, the Mark of the Beast, credit card companies, and the formula for Coca-Cola Classic all in the span of about a minute. Having grown up in evangelical churches in the US, I have definitely been an unwilling participant in these types of conversations on many an occasion. René and Martin smile and nod in exactly the same way that I used to. Brilliantly accurate.

The Passion play that Daniel has reworked and the other four actors have brought to life with him definitely pushes the envelope of what would be considered acceptable for an organization affiliated with the Catholic Church. He incorporates a lot of new findings and research from the time (1980s) and includes mention of Jesus being the son of a Roman soldier rather than the miraculously conceived Son of God. The narrators even call him Yeshua ben Pantera throughout the performance. (Pantera being the Roman soldier in question.) The Resurrection is also left a bit ambiguous. One part gives the impression that it didn’t happen while another short scene does include one of the Gospels’ Resurrection appearances. But anything other than blatant support for straightforward Catholic theology isn’t going to be accepted by such a hierarchical organization. The actors also get a bit daring with the Crucifixion scenes by depicting Jesus completely naked — no loincloth or anything — which is very likely more historically accurate. But male (or female) nudity is a pretty big no-no on Catholic property. I mean, they covered Michelangelo’s original nude paintings in the Sistine Chapel with flowing fabric. Michelangelo!

Needless to say, Father Leclerc is pretty upset about the liberties Daniel has taken with the modernization of the play and tries to shut them down. They do continue with their performances at the site, with adoring crowds supporting them, but the local Catholic hierarchy are not happy about it. They sometimes show up in the audience, and Daniel (as Jesus) directs his irritation at them in particular. The words and actions of the actual Jesus continue to converge with the performances of the actor portraying him.

The motif of a play within a play is a major element of Jésus de Montréal. It’s almost a play within a play within a play. Extremely meta. The film presents the narrative of Daniel and the rest of the outcast theatre kids pouring their creativity into an updated, modernized, and avant-garde rendition of the Passion story. There are scenes presenting the product of their work: we get to see the play too, not just the spectators within the film. It’s also an immersive play, so the actors interact with their audience. Daniel/Jesus hands out pieces of the multiplied bread to the crowd. He preaches directly to a 20th century audience while standing in the first century. Mireille/Mary Magdalene and Constance/Mother Mary converse with the crowd, giving them crucial information about daily life and culture in ancient Palestine. The audience is always small, so the performances are always intimate. It’s almost like interacting with the past while still existing in the present. Reaching back through the centuries to bring something forward into the here and now. The ancient story they are bringing to life begins infiltrating Daniel’s present life in new, interesting, and sometimes disturbing ways. The original Jesus story is somehow resurrected in Daniel, Constance, Mireille, René, and Martin; the past mixes with the present in a kind of mystical yet down-to-earth storyline. Human and divine coming together in an act of creativity.

Now back to the film’s depiction of the death and resurrection of Jesus. This is the last convergence of Daniel’s story with the Gospels. Due to an accident during their final (unauthorized) performance and poor (lack of) care given at the Catholic hospital, Daniel succumbs to the serious injuries he has sustained. He was taken to the second hospital, a Jewish one this time, half an hour too late to be saved. In the final mirroring event of the film, Constance gives permission to the doctors to turn Daniel’s body over to them. He apparently doesn’t have any family that they know of, and his organs and type-O blood can be used to saved others. This is the film’s interpretation of the Resurrection. Daniel’s healthy, 30-year-old heart is taken to a patient in the English-speaking world and his eyes are transplanted into an Italian patient. His (unintentional) sacrifice is universal in its ramifications, aiding individuals in concrete ways in other parts of the world, paralleling that of Jesus.

Daniel’s story in the film mirrors that of Jesus in outcome but not necessarily intentions. He didn’t set out to get mortally wounded while being (fake) crucified and then donate his body to help other people. His decisions, as well as those of others, just happened to lead to that conclusion. In contrast, Jesus is portrayed in the Gospels as very intentionally walking into the lions’ den while knowing there would be no supernatural protection for him. In John’s Gospel, he alludes to love driving this decision. He loves his friends and is willing to die for them.

This is my command, that you love each other as I’ve loved you. No one has greater love than this, the love that makes him lay down his life for his close friends’ sake. (John 15:12–13, The Gospels: A New Translation)

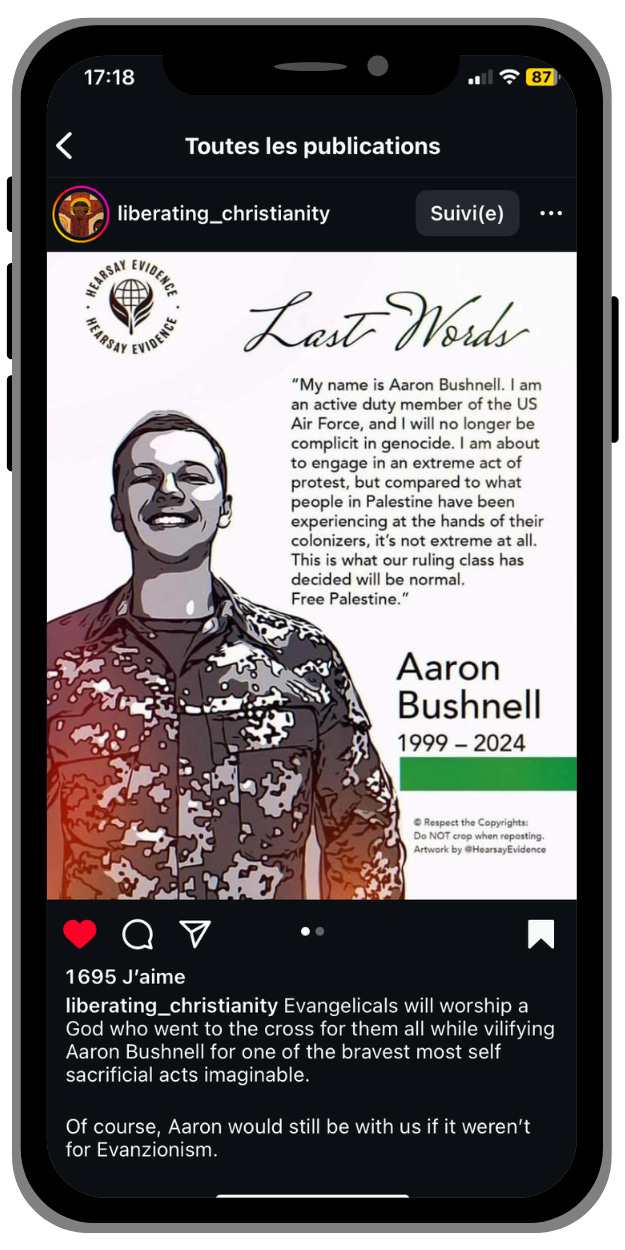

Many people — not most, but probably a lot — would die for their close friends. But what about people they don’t even know? Strangers? People they will never even meet? Would you? Would I? I don’t know. Someone this week did, though. On 25 February 2024, Aaron Bushnell self-immolated in front of the Israeli Embassy in Washington DC. Wearing his military fatigues and live-streaming on Twitch, he calmly described what he was going to do and why. And then he proceeded to do it.

Self-immolation is not a common form of protest, but it is a pivotal one. The self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức on 11 June 1963 in South Vietnam led to several other monks and nuns doing the same. Eventually, the regime they were demonstrating against ended and the Vietnam War came to an ignominious close. Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian vendor, set himself on fire on 17 December 2010 after years of frustration and the forced bribery required to make a living in his country. This one act inspired both the Tunisian Revolution and subsequent Arab Spring that swept the region in 2011.

After being harassed from childhood by the police for selling food in the streets, having his vendor’s scales confiscated, and being unable to afford further payoffs to the authorities, Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi went to the governor’s office, doused himself in accelerant, and cried, “How do you expect me to make a living?” before self-immolating in protest.

The final words of Thích Quảng Đức were written in a letter that he left behind for us:

Before closing my eyes and moving towards the vision of the Buddha, I respectfully plead to President Ngô Đình Diệm to take a mind of compassion towards the people of the nation and implement religious equality to maintain the strength of the homeland eternally. I call the venerables, reverends, members of the sangha and the lay Buddhists to organize in solidarity to make sacrifices to protect Buddhism.

And Aaron Bushnell, live-streaming on Twitch, was able to speak his last words to all of us:

My name is Aaron Bushnell. I am an active duty member of the US Air Force, and I will no longer be complicit in genocide. I am about to engage in an extreme act of protest, but compared to what people in Palestine have been experiencing at the hands of their colonisers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal. Free Palestine.

Anger, frustration, struggle, sacrifice, and hope for a better future are all elements of these three acts of extreme protest. But the fulfillment of that hope does not belong to Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi or Thích Quảng Đức or Aaron Bushnell. It belongs to us. One way or another, they all entrusted their dramatically public deaths to us, the public, to carry on the spark that they lit with their own bodies.

If you have paid attention to any kind of American media this past week, you might have noticed that those in power — whether politicians or corporate journalists — largely have no idea how to react to this act of protest.

Sending American soldiers to war — in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, or wherever else — is one thing they can support. The nameless, faceless soldier shown in military uniform and decorated with medals dying to “protect our freedoms” in some distant land. Trying to make the corporatization of warfare sound selfless and romantic. But an American soldier voluntarily self-immolating in protest of genocide and to draw attention to both Gaza and the Palestinian cause in general? It is incomprehensible to them. It is utterly selfless. I remember back when President Obama spoke highly of Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, even comparing him to Rosa Parks and America’s Founding Fathers. That their fight for freedom against oppression were all one and the same. That same ruling class now doesn’t know what to make of it now that they are complicit in our government’s current villainy.

You can see it definitively in this recent headline from The Washington Post. They know that most people only read the headlines — either because they don’t have the time or because they don’t have a subscription — so even if there were more information provided in the body of the article putting the event into context, the majority won’t get that far.

This headline, as you can see, portrays Aaron Bushnell as simultaneously far-right, far-left, and crazy. There’s something here for almost everyone to dismiss. But anyone who is willing to scratch just beneath the surface of Western corporate media’s “reporting” can easily catch glimmers of the underlying propaganda. I have yet to see anything concrete that shows he was crazy or suicidal. Self-immolation is not suicide. The outcome might be the same, but the intentions are not.

What could make someone sacrifice themselves like this? To selflessly give up everything to draw attention to something larger than themselves? Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi did it because of systemic economic injustice and corruption. Thích Quảng Đức did it because of the systemic brutality of the South Vietnamese regime against Buddhists. Aaron Bushnell did it because of our government’s involvement in genocide against an already stateless and brutalized people.

Maybe this is the Christ Mystery, the Divine Presence, the Buddha Nature, the divine in each of us as referenced in the Sanskrit greeting of Namaste. The best in each of us rises to the occasion and does what God, the Universe, the Collective Unconscious, whatever you want to call it, imparts what needs to be done.

One of my favorite theologians is Father Richard Rohr. His book The Universal Christ has been one of the most pivotal contributions in the development of my own spirituality thus far. In the introduction, he relates the vision of an English mystic.

In her autobiography, A Rocking-Horse Catholic, the twentieth-century English mystic Caryll Houselander describes how an ordinary underground train journey in London transformed into a vision that changed her life. I share Houselander’s description of this startling experience because it poignantly demonstrates what I will be calling the Christ Mystery, the indwelling of the Divine Presence in everyone and everything since the beginning of time as we know it:

I was in an underground train, a crowded train in which all sorts of people jostled together, sitting and strap-hanging-workers of every description going home at the end of the day. Quite suddenly I saw with my mind, but as vividly as a wonderful picture, Christ in them all. But I saw more than that; not only was Christ in every one of them living in them, dying in them, rejoicing in them, sorrowing in them — but because He was in them, and because they were here, the whole world was here too, here in this underground train; not only the world as it was at that moment, not only all the people in all the countries of the world, but all those people who had lived in the past, and all those yet to come.

I came out into the street and walked for a long time in the crowds. It was the same here, on every side, in every passer-by, everywhere — Christ.

I had long been haunted by the Russian conception of the humiliated Christ, the lame Christ limping through Russia, begging His bread; the Christ who, all through the ages, might return to the earth and come even to sinners to win their compassion by His need. Now, in the flash of a second, I knew that this dream is a fact; not a dream, not the fantasy or legend of a devout people, not the prerogative of the Russians, but Christ in man …

After a few days the “vision” faded. People looked the same again, there was no longer the same shock of insight for me each time I was face to face with another human being. Christ was hidden again; indeed, through the years to come I would have to seek for Him, and usually I would find Him in others — and still more in myself — only through a deliberate and blind act of faith.

The question for me — and for us — is: Who is this “Christ” that Caryll Houselander saw permeating and radiating from all her fellow passengers? Christ for her was clearly not just Jesus of Nazareth but something much more immense, even cosmic, in significance. (The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe pp. 1–3)

Maybe this is what Jésus de Montréal was trying to portray in its avant-garde interpretation of an updated and innovative Passion play. The Eternal Story being replayed over and over again in new, enigmatic, and unexpected ways. The Christ that, as Caryll Houselander perceived, is somehow a part of everyone, hidden yet present in a constant process of unfolding. The story of the Cosmic Christ or the Universal Buddha being uncovered and brought to life in an endless progression of developing humanity. The story of love and self-sacrifice, whether in first century Palestine, South Vietnam in 1963, Montreal in 1989, Tunisia in 2010, or Washington DC in 2024. Now it’s our turn to unfold.