I really got to brush up on my Italian language skills while watching this week’s movie. The only versions I was able to find online were the original Italian without any subtitles or dubbed into English. I despise dubbed films; give me the original even if I don’t know a single word in the language. Thankfully I spent part of my junior year studying Italian in Rome and still remember enough of it 20 years later. The sparse dialogue is also taken almost entirely from the New Testament, so it wasn’t all that difficult to figure out the context of each scene.

The Gospel According to Saint Matthew is the oldest film in this Lenten series, dating all the way back to 1965. Its stylistic elements are quite a jarring departure from both Monty Python’s Life of Brian and The Savior. Famed Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini created this film in the stripped-down style of Italian neorealism. Although films were frequently made in color by the mid-1960s, this one was shot in simple black and white. It was filmed entirely on location in the southern Italian region of Calabria. It uses a non-professional cast. The landscapes are rough, rustic, and rural. The actors are wearing homespun fabric sewn into modest, uncomplicated clothing. There is a lot of emphasis on the local people. Not specific characters really, but just the peasants in the background as they go about their lives. Working in the fields. Taking care of children. Fishing on the lake. Buying food in the market. Even the city scenes have an undeveloped, primitive quality about them since it looks like they were all filmed in the ruins of ancient Rome that dot the landscape all around the Mediterranean. The film is as much about the everyday people that populated ancient Palestine as it is about its famous protagonist.

The cast being entirely non-professional, many likely without any acting experience at all, the scenes are pared-down, raw, and instinctive. Naturalistic emotions and reactions punctuate the long, scattered silences. There are hardly any special effects, and obviously no computer-generated ones. The scene of Jesus walking on water contains the height of special effects in the film, and it’s mostly all wide shots. No close-ups to see by chance how they pulled it off. The music Pasolini chose to accent the film is also intriguing. He compiled an eclectic array of songs from a wide variety of sacred and religious belief systems. There are arrangements from Bach in the Christian West, Jewish ceremonial music, and African songs from the Congo. But being American, the two genres that stood out the most to me were the recurring Black spirituals and folk/bluegrass selections. Two genres of struggle. Spirituals are the African American songs of struggle against systemic racism, prejudice, and inequality. Folk and bluegrass are the music of the working class in its struggle against poverty, oppression, and exploitation.

Just as with all other roles in the film, that of Jesus is also filled by a non-professional actor. He is played by Enrique Irazoqui, a 19-year-old communist activist from Barcelona who was studying economics at the time. As a Time article from the era described Pasolini’s directorial decisions, Irazoqui was sent “out to preach among the peasantry with a social revolutionist’s fervor.” And Jesus very much comes across as an activist and even a revolutionary in this film. Irazoqui in the role has a similar look, feel, and energy to Che Guevara, who was a well-known revolutionary at the time this film was made. The text is lifted almost entirely from the Gospel of Matthew (hence the title) which to Pasolini was the most realistic of the four. Being a Marxist himself, Pasolini wanted an earthy, realistic, pared-down depiction of Jesus that limited the sentimentality and mysticism of the other gospels.

Most of Jesus’ teachings and parables that are included are practical, everyday, and even anti-dogmatic. There isn’t much of an emphasis on what to believe but rather on what to do.

Because of this, I say to you: don’t worry about your life, as to what you’ll have to eat [or what you’ll have to drink], or about your body, as to what you’ll have to clothe it. Isn’t life a greater thing than food, and the body a greater thing than clothing? Take a good look at the birds in the sky: they don’t sow seed or reap grain or gather it into barns; but your father in the sky feeds them. Aren’t you worth far more than they are? (Matthew 6:25–26, The Gospels: A New Translation)

Don’t supposed that I’ve come to bring peace to the earth; I’ve come not to bring peace, but a sword. I’ve in fact come to divide a man from his father and a daughter from her mother and a bride from her mother-in-law; and a person’s enemies will be members of his own household. (Matthew 10:34–36, The Gospels: A New Translation)

Iesous said to him, “If you want to be as you were meant to be, then go and sell everything you have and give the money to the destitute, and you’ll have a storehouseful in the skies, and come and follow me.” But when he heard this condition, the young man went away, stung, as he possessed a great deal. (Matthew 19:21–22, The Gospels: A New Translation)

Instructions for daily life and how to live alongside others. Recognition that restructuring society into one based on love, mutual aid, and solidarity is going to cause divisions. Even the scene showing the multiplication of loves and fishes can be construed as a miracle of sharing and distributing the food that was already present and available among the crowd rather than a supernatural event of food appearing out of nowhere. It’s also evident that the only thing that supremely pisses Jesus off is the exploitation and abuse of the poor and marginalized. He goes ballistic in the temple courtyard immediately after the popular uprising of the Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem, throwing the marketplace into disarray and inviting the ire of the religious and economic authorities. Pasolini’s Jesus always sound a lot angrier and more passionate than other depictions, which is probably why he chose Matthew’s gospel. It’s much more focused on economic justice and social solidarity than the other three.

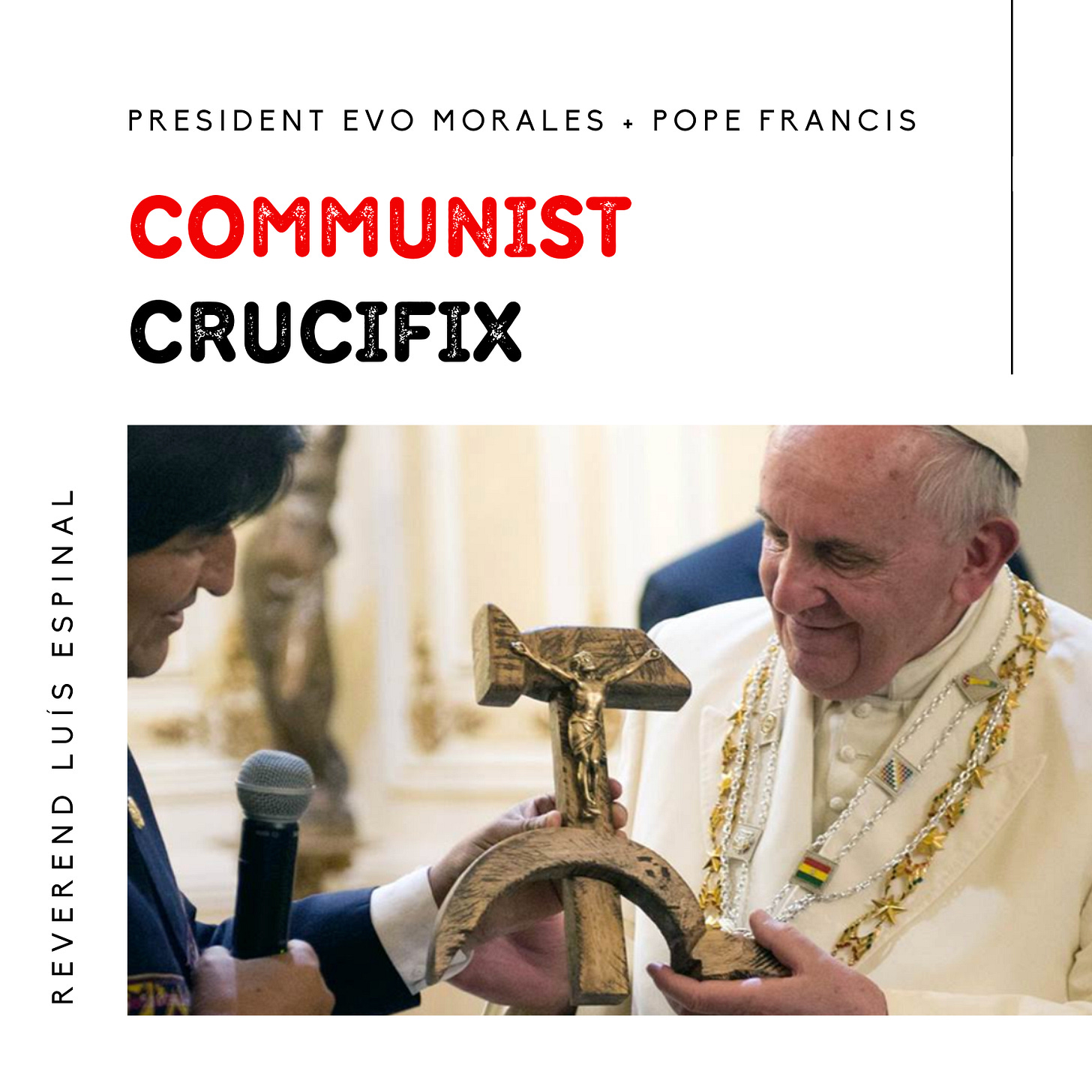

When it comes to economic justice and social solidarity in the modern world, the current leader of the Roman Catholic Church has been unusually supportive of labor movements and leftist critiques of capitalism. Ever since he was elected to the pontificate in 2013, Pope Francis has been making positive comments about labor unions, the evils of unrestrained capitalism, and the similarities between Christian and Marxist arguments.

“I can only say that the communists have stolen our flag. The flag of the poor is Christian. Poverty is at the center of the Gospel. Communists say that all this is communism. Sure, twenty centuries later. So when they speak, one can say to them: ‘but then you are Christian.’” — Pope Francis

He has even referred to modern finance and the global economy as terrorism “against all humanity.” Pope Francis has repeatedly warned governments against the exaltation of the false gods of money, finance, and greed at the expense of the weak and vulnerable. He has drawn comparisons to extremist movements of the 20th century that discarded the imperfect as nuisances and dangers to society. What does the unrestrained capitalism and corporatism of the West practice if not this as well? Usually a less explicit, in-your-face form, but it’s the same root problem of disposable humanity being expressed in political, social, and economic systems.

The pope has also championed solidarity as being both a moral virtue and “a requirement of justice, which requires correcting distortions and purifying the intentions of unjust systems, as well as radical changes of perspective in the sharing of challenges and resources among men and among peoples.” Essentially the opposite of everything the globally dominant systems of capitalism and corporatism that most of the world lives under, whether in the Global North or the Global South. We are all being exploited, the poor and ever-shrinking middle classes in the North or basically everyone in the South. Apart from the very top percent of those who have managed to hoard obscene amounts of wealth at the expense of billions.

It is no surprise that Pope Francis is supportive of workers’ movements and, for a pope, so critical of modern capitalism. He was ordained a Catholic priest in Argentina in 1969 and served as head of the country’s Jesuit order during the military coup and subsequent years of its right-wing dictatorship.

As it happens, I am currently reading The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism by Naomi Klein. (Although I am not yet finished at the time of this writing, I highly recommend.) In a nutshell, this massive book dissects the use of shocks (economic, social, natural, etc.) to disorient a society and implement drastic systemic changes before people can find their balance and register their disapproval. Sometimes these shocks are deliberately planned, like the coup d’état in Chile against President Allende and the following Pinochet dictatorship, but they can also simply be unplanned or unexpected events that are taken advantage of by those in power. This happened to the public school system in Louisiana following Hurricane Katrina; it was almost entirely privatized instead of rebuilt. This was due to a natural disaster. It also happened in the United States following the September 11th terrorist attacks. I don’t buy into the conspiracy theories that the Bush Administration planned the attacks themselves, but I do think they took advantage of the situation in its aftermath to push through policies that the American public would never have approved of otherwise. The illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Patriot Act being two such examples.

I was reading through the sections covering Argentina’s collapse into authoritarianism in the mid-1970s when I watched The Gospel According to Saint Matthew. The book had covered a few other Latin American countries in detail before I got to the Argentinian section, as well as the critical role that both the CIA and Milton Friedman’s University of Chicago economists played in destabilizing this entire region of the world. I hadn’t known much about this history before beginning The Shock Doctrine. Just the broad outlines, but no details. I knew the US government was somehow involved, but I didn’t know how. I knew the fear of communism and desire to expand capitalism played a role, but I wasn’t sure of the specifics. Reading through this explication of history, the details were worse than I had previously imagined. Especially in conjunction with this Marxist-tinged version of Matthew’s gospel.

The economic policies that were so ruthlessly pursued in the Southern Cone countries of Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Bolivia in the 1970s and 1980s were dreamed up by Friedman at the University of Chicago. Today we would call them neoliberalism, or sometimes Reaganomics in the US since President Reagan really amped up their implementation in the 1980s. Similar to Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister in the UK during the same period. Both Reagan and Thatcher (and their successors) implemented these neoliberal policies more slowly in the Western developed world, but they were rammed through in quick succession in countries like Chile and Argentina. Those who voiced disapproval were assassinated, tortured, or disappeared by those in power.

While the policies attempted to excise collectivism from the culture, inside the prisons torture tried to excise it from the mind and spirit. As an Argentine junta editorial noted in 1976, “minds too must be cleansed, for that is where the error was born.”

Many torturers adopted the posture of a doctor or surgeon. Like the Chicago economists with their painful but necessary shock treatments, these interrogators imagined that their electroshocks and other torments were therapeutic — that they were administering a kind of medicine to their prisoners, who were often referred to inside the camps as apestosos, the dirty or diseased ones. They would heal them of the sickness of socialism, of the impulse toward collective action. Their “treatments” were agonizing, certainly; they might even be lethal — but it was for the patient’s own good. “If you have gangrene in an arm, you have to cut it off, right?” Pinochet demanded, in impatient response to criticism of his human rights record. (The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism p. 138)

Individualism has been the norm for so long in the West, and especially in its anglophone countries, that we often forget there is anything else. American culture is so aggressively individualistic that experiencing something different can come as a bit of a shock. I sensed the difference when I first moved to South Korea, but it wasn’t until I had learned the terminology of collectivism and individualism that I began to understand the difference. Even in France, which is still Western although not anglophone, there are far more elements of collectivism ingrained in the culture. Even when there is massive dysfunction from labor strikes and protests that upend commutes to work or travel itineraries, most French people are angry at the government rather than their fellow citizens. Solidarity. Collectivism. Working together. This is what extremist neoliberal economic policies under a military junta in Argentina wanted to eliminate through the use of both economic shocks and the shock of torture.

In testimony from truth commission reports across the region, prisoners tell of a system designed to force them to betray the principle most integral to their sense of self. For most Latin American leftists, that most cherished principle was what Argentina’s radical historian Osvaldo Bayer called “the only transcendental philosophy: solidarity.” The torturers understood the importance of solidarity as well, and they set out to shock that impulse of social interconnectedness out of their prisoners. Of course all interrogation is purportedly about gaining valuable information and therefore forcing betrayal, but many prisoners report that their torturers were far less interested in the information, which they usually already possessed, than in achieving the act of betrayal itself. The point of the exercise was getting prisoners to do irreparable damage to that part of themselves that believed in helping others above all else, that part of themselves that made them activists, replacing it with shame and humiliation. (The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism p. 138)

Collectivism and solidarity are both far more common in Latin American cultures, and not just among leftists. If you have never visited a non-anglophone and/or non-Western/Global North country for an extended period of time, then you probably have no idea just how deeply individualism is ingrained in our culture. And not just individualism, but toxic individualism. This is probably one reason that rampantly unrestrained capitalism does so well in the US and many of our anglophone sister nations. But other regions of the world are different. In Argentina, they tried to literally torture the solidarity out of people.

The ultimate acts of rebellion in this context were small gestures of kindness between prisoners, such as tending to each other’s wounds or sharing scarce food. When such loving acts were discovered, they were met with harsh punishment. Prisoners were goaded into being as individualistic as possible, constantly offered Faustian bargains, like choosing between more unbearable torture for themselves or more torture for a fellow prisoner. In some cases, prisoners were so successfully broken that they agreed to hold the picana on their fellow inmates or go on television and renounce their former beliefs. These prisoners represented the ultimate triumph for their torturers: not only had the prisoners abandoned solidarity but in order to survive they had succumbed to the cutthroat ethos at the heart of laissez-faire capitalism — “looking out for №1,” in the words of the ITT executive. (The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism p. 139)

Taking in this paragraph was quite shocking. How could anyone think that gestures of kindness, love, and sharing ought to merit punishment and torture? Aren’t those clearly good things? Things that should be reinforced? It’s like that classic Mitchell and Webb sketch, “Are we the baddies?” Did the torturers never take a step back and think to themselves, “As torturers, do we really have the moral high ground here?” It’s just such an absurdist caricature of (im)morality, flying in the face of all those “do unto others” and “love your enemy” teachings. Just blatant evil. The “cutthroat ethos at the heart of laissez-faire capitalism” is directly opposed to the Sermon on the Mount and the parables of Christ. Especially as they are depicted in The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.

As I have read more over the years about both early and non-Western Christianities, the more I have realized just how much of an outlier evangelicalism as practiced in the United States really is. Take for example the whole “Jesus is my personal savior” theology, extremely common in Western non-liturgical churches but almost unheard of anywhere before the 20th century. In reality, it is little more than certain Christian dogmas turned into a commodity and sold to the masses. Jesus becomes a product, a cure, a “free gift” that is often sold for profit down the line through subscriptions, support letters, and calls for donations.

Theologian Dorothee Sölle makes this argument this in her book Thinking About God: An Introduction to Theology.

One of the catastrophic consequences of capitalism is what it does to rich people at the heart of this economic system by reducing humanity to the individual. One can see how American commercialism presents all items as being ‘quite personal to you’, even if millions of them exist. Your initials must be on your T-shirt, on your ball-point pen, on your bag–and on your Jesus. He too is quite personal to you. The spirit of commercial culture is also alive in this religion: for fundamentalism, which is massively effective, Jesus is ‘my quite personal Saviour’, and really no more can be said than that. The confession of ‘Jesus Christ — my personal savior’ brings no hope to those whom our system condemns to die of famine. It is a pious statement which is quite indifferent to the poor and completely lacking in hope for all of us. In the light of this individualistic reduction we must put the question of christology ecumenically and ask about Jesus Christ ‘for us today’ in the age and place in which we live.

Discipleship. Learning spiritual practices. Helping the poor. Very little emphasis was placed on any of these things in the youth groups and parachurch organizations I attended in the 1990s and early 2000s. The priority was numbers. Bring your friends to church so they can get saved. But then that was it. Little to no follow-up. It was always a growth and expansion game, but not in quality. Only in quantity. More, more, more. But in the end, very few of those kids who got saved at Friday night lock-ins or summer camps or Wednesday nights stuck around or developed any meaningful kind of spirituality. Christian nationalists in the US, most of whom are evangelical and/or fundamentalist, love to blame atheists, feminists, the LGBTQIA+ community, and anything else deemed too “woke” for the country’s declining church attendance. But in reality, it has largely been the fault of a commercialized, capitalistic, and cruel Christianity. People want community, not commodities.