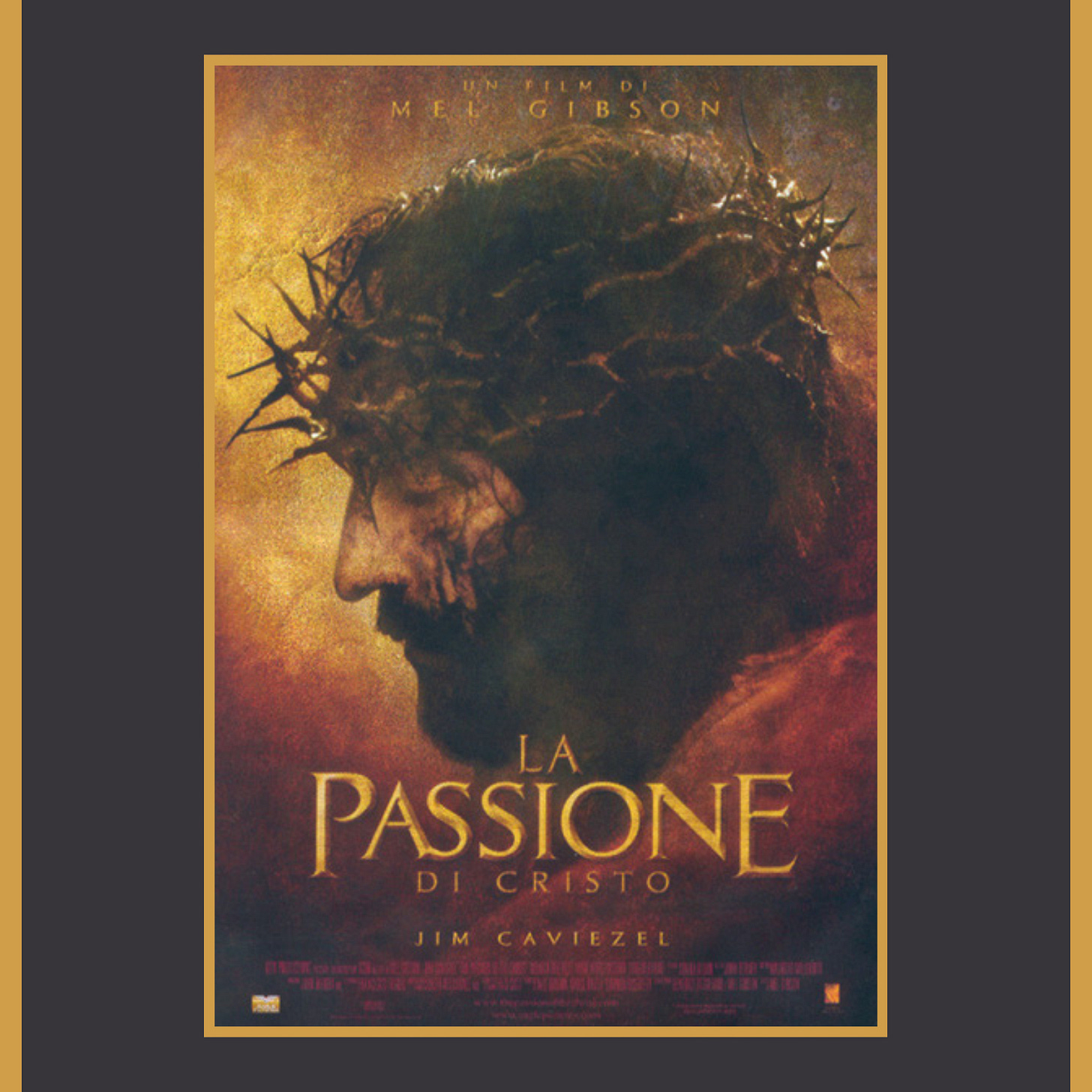

We are at the penultimate entry in this Lenten series, and this has been the most sensitive, intricate article I have written thus far. Hence the length. It is also my least favorite of these eight films. While I saw The Passion of the Christ in cinemas twice and watched it a handful of times on DVD, I haven’t seen it for well over a decade. It hasn’t aged well. I had forgotten just how relentlessly brutal and shockingly violent it is. And it’s such a strange film. I don’t want to say that I hate it because it does have a few redeeming qualities, but overall, it is neither a helpful nor inspiring film. From a filmmaking, storytelling perspective, it has essentially no character development. It’s just a marathon of blood and gore that doesn’t change the path that the main character is travelling down. It IS the path he’s travelling down. If you did not already have some basic familiarity with the story of Jesus — who he was, his teachings, his historical significance, and the religion that has been built up around him — you would be at a loss for words while watching The Passion of the Christ. What is it even about? There is barely a traditional plot or story structure; it’s just an endless experience of visceral shock. That’s why I refer to it as torture porn. It isn’t telling a story, not really. It’s simply frame after frame and scene after scene of unending torture created to induce a jarring, emotional reaction in the viewer. It is not uplifting. It is not instructional. It is not inspiration. It isn’t even hopeful until maybe the last 30 seconds of the film. I used to call it a religious snuff film because that’s almost what it is. Sure, it involves actors. But the entire point of the film is a long, drawn-out murder. It is an unrelenting glorification and even worship of the god of violence.

The Passion of the Christ was released internationally in the midst of my first real deconstruction. I was spending my junior year of college studies away from my home university in the United States, taking one semester in Paris and then another semester in Rome. I suddenly did not have mandatory chapels to attend at my Methodist university. For the first time in my life, I was not attending an Americanized evangelical church two or more times per week. I had found an English-speaking Protestant church in Paris and attended a weekly Sunday evening service, but it was a very international congregation. There was no patriotic flag worship or America-centric theology intertwined with hymns and biblical texts. It is extremely common in the US to find American flags and other national iconography in churches. It is also very common within evangelical spheres, especially in the years following September 11th, to witness a sort of hero worship of firefighters, police, and military. There was a blatant mixing of reactionary religion with authoritarian politics that eventually came to fruition with Donald Trump and the rise of MAGA in 2015–2016. But none of that was present at the church I attended for four months in Paris. The trappings and allure of White evangelicalism began to fall away in the City of Light. By the time I got to the Eternal City in January 2004, I was becoming even less interested in organized Christianity. I did try out an English-speaking Baptist church near my apartment for two or three Sundays, but it just was not my cup of tea. I sat in the back and found the music insipid and the sermons boring. I stopped going and began wandering into some of the (mostly empty) Catholic churches that dot the cobblestone streets of Rome. They were silent, peaceful, and echoed with history. Or they were majestic and grandiose, welcoming pilgrims from every corner of the world. Since I was taking an art history course that met all over the city, I was able to see and learn about every major Roman cathedral. Saint Peter’s Basilica. San Giovanni in Laterano. Santa Maria Maggiore. Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. The Pantheon. Basilica di San Clemente in Laterano. Santa Maria in Trastevere. Santa Maria della Minerva. I loved the art, the spirituality, the history, the connection to saints and sinners from centuries past in the quiet spaces these buildings offered.

While The Passion of the Christ had been released in the US on Ash Wednesday, it didn’t come out in Italy until Holy Week. There had been a couple months of intense buildup and publicity that were now washing ashore and making waves in Europe. My grandpa had even sent me an email about how wonderful, inspiring, and biblical the film was. Implying that I should see it when it was released in Rome. That week happened to be spring break, and all of my roommates had left for other destinations around Europe. I stayed behind because my parents were visiting. I had actually been able to get tickets to Easter Mass in Saint Peter’s Square for all three of us. The tickets were free, but you had to reserve them beforehand because the crowds can get huge. This was in 2004, so it ended up being Pope John Paul II’s final Easter Mass. He died the following year. There were so many people from so many different countries, cultures, languages, and backgrounds celebrating together. I wasn’t Catholic at the time, so I couldn’t really follow the sequence of the mass all that well. But it was an incredible experience. Within a few days of each other, I had attended my first Catholic Easter Mass and seen this Catholic-infused Hollywood movie. I first saw it alone at a cinema with Italian subtitles. I remember being in a state of numb shock when walking out of the cinema and heading back home. WTF had I just watched? For days afterward, I felt like I was moving in a sort of trance. I must have been in some kind of low-level internal distress for several days, processing the scenes of violence and torture I had witnessed.

Once all seven of my roommates had come back from spring break, most of them wanted to go see what all the fuss was about with this movie. I hadn’t intended to go again, but we found a cinema showing the film with English subtitles. This was only my second semester of college Italian, so the Italian version I had seen initially was difficult to follow. I didn’t know a bunch of the verb tenses yet, and the subtitles changed too quickly for me to read the entire line. So I went with them to see it a second time. My roommate who shared an actual room with me, Jen, was the only somewhat serious Catholic in the apartment and was the most gung-ho about seeing this Catholic film. As soon as we got into the cinema, they all made a beeline for the concessions. I tried to warn them against buying anything to eat during this movie. I had already seen it once and knew it was definitely not a popcorn flick. None of them had any idea just how relentlessly violent this film was going to be. We all sat in a row toward the middle of the theatre, and as the minutes passed and the scenes grew more violent, everyone began shifting more in their seats. Setting down the unfinished popcorn and candy. Looking away. Covering their eyes. Gasping. Jen had really been looking forward to seeing this religious film for the past several weeks; she walked out during the scourging scene. She made it less than halfway through before throwing in the towel. She met us back at the apartment once the film was over. It was way too much for her. It was way too much for a lot of people.

But it isn’t all negative; The Passion of the Christ does have its positive points too. The score is absolutely stunning. I bought the CD at a bookshop in Rome and listened to it as study music and going-to-sleep music for years afterward. It is honestly one of the best movie scores around, right up there with basically any Hans Zimmer, Philip Glass, or Ramin Djawadi soundtracks. The cinematography is beautiful, especially the night scenes in the Garden of Gethsemane with the blue moonlight filtering down through all of the olive trees’ branches. The costumes are realistic. The hair, makeup, and prosthetics are all very well done. All that kind of technical moviemaking stuff actually makes The Passion of the Christ the most sophisticated among the eight films I’ve chosen for this series. But that doesn’t make it the best.

I will address the one major negative point I have with the film in a minute, but I’ll start with a few of the minor ones. I remember when I first heard about this film while in production, it was being described as aspiring to be the most historically accurate depiction of the life of Christ ever made. From historical sources to the use of dead languages and everything. It wasn’t. It was far closer to a typical medieval passion play (like from the actual Middle Ages) than anything from Antiquity. For example, the Jewish characters speak Aramaic. Which is good! That’s actually very accurate. But the Roman characters speak Latin. Normally, Romans would only have spoken Latin if they were living near Rome. But they weren’t. They were all living in Palestine. Latin wasn’t the lingua franca of the ancient Mediterranean world, especially in the east. Later on, when the Roman Empire split into two, the Byzantine Empire in the east used Greek. It’s why the Eastern Orthodox churches don’t use Latin. They were never in the Latin-speaking Western Roman Empire. Most of the imperial soldiers at the time would have been from Syria or other neighboring provinces. Not from the Italian peninsula. Thus they would have mainly spoken Greek and probably some Aramaic, but not Latin. And Jesus busting out the fluent Latin with Pilate? Highly unlikely. He probably knew enough Greek to carry on a conversation, but Latin would really be pushing the historically accurate limits. Plus they used ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation in the film rather than classical Latin. No one would have been speaking church Latin before the church even existed. And then there are all of the torture devices and accoutrements having to do with the scourging, Via Dolorosa, and the methods of crucifixion itself. They were all much more medieval and Renaissance in their depictions than ancient. Archaeologists and historians have figured some of this stuff out from ancient sources and dig sites, but none of that was depicted. The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus of Montreal were both more historically accurate in their adaptations in this regard. The film opted to have Jesus carry a full-size cross (utterly impossible), nails through the palms of his hands (medical researchers have shown this to be unworkable), the use of a footrest (invented by artists during the Middle Ages), and a very high t-shaped cross (ancient graffiti show a low T-shaped cross).

A lot of these conscious decisions, artistic liberties, and extra-biblical additions were derived not from original sources or new historical research, but rather from an 18th and 19th-century mystic whose visions might have been exaggerated or even fabricated. The biblical text itself is very bare; none of the Gospel writers give many detailed descriptions about what’s happening. They assume the audience has seen a crucifixion and doesn’t need any elaboration. But for 2004 moviegoing audiences, we needed those blank spaces filled in. However, they were filled in by some medieval-inspired fever dreams from the early 1800s. That’s why the film comes across as some kind of medieval passion play. Because that’s what it is! Complete with all of its anti-Semitic imagery and racist tropes depicting the enemies of Jesus as extremely stereotypically Jewish (in the most negative ways) while Jesus and his crew (who are also all Jewish) look like they hail from southern Europe. It’s almost comedic in its use of caricatures. Almost.

This is kind of nitpicky, but one of the most obnoxious things that I had forgotten all about was the use of two (near) dead languages. Not their use specifically, but the accents of the actors when speaking them. For the most part, the Latin comes across pretty solid. A lot of people have a basic familiarity with Latin to some extent, and a big chunk of the cast were Italian actors. Italian is, to some degree, just modern Latin. So the accents were pretty uniform with this language because the actors either spoke Italian as their native language or they had some familiarity with it because it’s still used in the Catholic Church to this day. But the Aramaic? It was not so uniform. Most of the characters sounded okay when speaking it since they mostly all had the same base accent of Italian or Romanian or some other Romance language. But Jesus? His accent when speaking Aramaic, which he does almost the entire time he has lines, sounds decidedly American. It’s almost like that scene in Paris, je t’aime when Margo Martindale’s character is walking around the city describing her experiences in French voiceover with a horrific American accent. It works because it’s meant to be comedic and heartwarming. She loves Paris, and she’s just trying really hard to learn the language and enjoy the city. In contrast, Jesus speaking his native Aramaic in a torture flick is not supposed to be comedic and heartwarming. The overly obvious American accent is just kind of cringe. Although it’s the very least of the cringe in The Passion of the Christ.

The major negative point of this film is its glorification of violence, of the somehow superhuman ability of this version of Jesus to survive torture that would have killed literally any other human being. The amount of blood loss is just not realistic. I remember reading a few articles at the time from medical professionals that discussed this, particularly in regards to the scourging scene. Humans simply can’t lose that quantity of blood and continue living. I remember the first (and only) time I tried to donate blood. I don’t have any kind of phobia about needles or blood. I don’t want to sit there and watch the needle go into my vein, but the idea itself doesn’t really bother me. I went with a couple of friends to the Puget Sound Blood Center one afternoon and didn’t end up leaving for almost three hours. After only about 30–45 seconds, I started to black out. My ears were ringing and stars began to enclose my vision. They hadn’t even taken that much blood yet. Probably not even a quarter of the necessary amount. While I am a generally small person (5’1”/155cm), that really isn’t much blood at all. A single donation is roughly one pint (about 500ml), and I had probably lost about 100ml. I couldn’t even sit up without starting to black out again for three hours. The nurses had to give me a packet of saline just so I could walk out of there semi-conscious. Compare my experience to the scourging sequence in The Passion of the Christ. There was a good liter of blood or more on the ground by the end of it, and then you have the entire Via Dolorosa and Crucifixion itself to get through with even more extensive blood loss.

This over-the-top violence dehumanizes Jesus in two ways. First, torture itself is dehumanizing. Think of all of the videos we have seen over the years of (predominantly) Black men being attacked, tortured, or murdered by police. Rodney King. Philando Castile. George Floyd. The ignominy of having your final moments preserved on film for everyone to see. The Passion of the Christ does the same with Jesus even though it’s actors and not the actual footage. That’s why it comes across as a religious snuff film. But it also dehumanizes Jesus by having him come across as some kind of superhuman entity. No mere human could withstand this kind of prolonged torture. From the excessive scourging with unrealistic blood loss to the 300-pound cross (literally impossible to carry in any kind of physical condition), the film portrays Jesus as a sort of Herculean demigod. Seen through this veneer of endless dehumanizing torture, we can’t relate to him anymore. For example, about halfway through the scourging scene, Jesus is on his knees, seemingly at the end of his strength. Mother Mary makes her way through the crowd and makes eye contact with her son. This somehow gives Jesus the strength he needs to stand back up, ready to take more punishment. It almost seems like he’s baiting the guards to continue their frenzied lashing. The soldiers are definitely sadists, but Jesus comes across here as almost masochistic. He’s daring them to continue their torture, and they do.

While the violence is excessive and unrelenting, of all the Jesus films or series I’ve ever seen, it is the one where I relate to the character of Jesus the least. There is so little emphasis on character development or who this person even is that we just don’t relate to him as much. This is the same for basically all of the other characters as well. We see extremely little to zero interaction between them at all. Of the 126 minutes in the film, about 95% of them are just an absolute onslaught of torture. We get one scene with adult Jesus and his mother, as well as one tiny, dialogue-less scene with toddler Jesus and his mother. Same with Mary Magdalene. There is no dialogue when she and Jesus meet either, and she is incorrectly identified as the woman caught in adultery. But this misidentification is pretty common for Jesus films, so I’ll let that one slide. The main issue is, if we barely know who these people are, then why would we care about their relationships with each other? The handful of scattered flashbacks are insufficient to build meaningful connections between the characters but also between the characters and us, the audience. This is where longer-form productions like The Chosen succeed. They are building in-depth relationships among a wide array of characters so that once the show finally reaches the events portrayed in The Passion of the Christ, it will be that much more harrowing. As this film stands, we don’t really know the characters very well at all, so we don’t care as much about what happens to them.

The Passion of the Christ is, by far, the most violent film I have ever seen. And the violence doesn’t really serve any purpose in the telling of the story. If you can even call it storytelling. It’s just a two-hour torture-fest. However, it does leave out one particular type of suffering that Jesus most likely experienced. Suppresses it, actually. And this is not a criticism of the film; it’s a criticism of Christianity overall. A few years back, maybe 2018 or 2019, I came across a blog on Patheos about the sexual humiliation and abuse that was almost certainly a part of Jesus’ torture, and perhaps even sexual assault. It was extremely shocking, and my thoughts kept returning to it during Lent that year. I read the blog, as well as the original scholarly paper that it references. How had I never heard of this before? I grew up being subjected to graphic descriptions of the death of Jesus in a variety of religious spaces. From childhood through adolescence until I stopped regularly attending either evangelical or Catholic churches when I left the US in 2010. I can understand not bringing it up with children, but college students? Adults? This idea had never been broached, never even hinted at, in either the Protestant or Catholic domains I had frequented.

But once you go through the reasoning and re-read the texts, it’s so obvious. The sexual humiliation is in the biblical accounts themselves. Stripping, forced nudity; those are elements of sexual humiliation. It can also be surmised — and David Tombs surmises it — that Jesus could very well have been sexually abused or even sexually assaulted as well. Crucifixion itself could be understood to be a type of prolonged, emasculating sexual assault. It would not be much of a stretch to reach this conclusion. The elements are all there, even in the unembellished reading of the Gospels, but I had never before put the pieces together. Nor had any pastor, priest, or other Christian leader in all the decades I had regularly attended churches and other religious spaces. Why? Why the suppression?

I think a lot of the reason is shame. Christianity has a long history of difficulties with sex stuff. Going all the way back to the writings of Saint Paul which make up about half the books in the New Testament. These were probably poorly translated and even more poorly interpreted, but still, a lot of the problematic sentiment stems from him. And then there were all of the later church teachings about things like celibacy, same-sex relationships, women, abortion, abuse, etc. A lot of this is taboo within Christian circles. Which is probably why it took decades — if not centuries — for the rampant sexual abuse of women and children to finally come to light. When Sinéad O’Connor ripped up that picture of Pope John Paul II on SNL, she was globally crucified for it. But if she had done it only a few years later, she might have received a bit of applause instead. In 1992, the general public was not yet aware of the widespread mental, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse meted out mostly to children and then covered up by church hierarchy in order to elude authorities and escape consequences. In 2021, a report in France concluded that 330,000 children had been sexually abused in the country over the past 70 years. And it isn’t just the Roman Catholic Church either. Guidepost Solutions released the results of their independent investigation into the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) in 2022. A detailed list of victims maintained by the SBC runs to over 200 pages. Not 200 victims. Two-hundred pages of victims. Since 1998.

It is endlessly ironic that these various branches of Christianity suppress both the sexual violence they have committed against their own members (most of whom were children at the time!) as well as the obvious evidence that Jesus Christ himself was sexually humiliated and abused, if not also sexually assaulted. Organized Christianity — and by extension a lot of Christians from all kinds of backgrounds — are not equipped to deal with sexual violence committed against them or their loved ones because of the overwhelming shame that has been ingrained into us surrounding it.

I have two examples of this from my own evangelical megachurch. I attended this church regularly between 1989 and 2003, and there were at least two major scandals involving sexual misconduct and abuse. The first one involved the head pastor who had also founded the church in the 1970s. He was accused of molesting multiple men on their wedding day or before their baptism, usually just before the ceremony. It was covered up for years, decades even, until it all came tumbling out. I was only about 14 or 15 when this happened, but I remember how the congregation was simply unable to cope with not only the idea that he had actually repeatedly done this but also the sense of betrayal once it was generally accepted that he was a sexual abuser. The accusations were explained away as spiritual warfare, supernatural attacks by Satan and his demons, lies from the media, and whatever else to avoid confronting reality. As soon as he had stepped down and left the church, no one talked about him anymore. It was covered up. Ignored. Suppressed. Later on, there was another scandal involving a junior high adult leader and at least one kid in the youth group. I was in high school by then, but I had known this leader quite well in my own junior high days. The entire situation was kept so hush-hush that to this day, I have absolutely no idea what actually happened. All I know is that he ended up going to prison for a while and is now a registered sex offender. In neither situation was there any sort of frank discussion about what had happened, what steps were being taken, how to protect yourself from abuse, or what leadership was doing to make sure nothing like this would happen again. We were taught to be ashamed and ignore the stigma of sexual scandal in the church. This type of abuse is extremely common within Christian churches of all kinds (and probably other religions too). It is systemic, and Christians are largely ill-equipped to process or handle the fallout from such abuse and betrayal.

There’s going to be a hard re-direct here, but I promise it will tie in with everything else by the end. I’m going to introduce a concept that you might not have ever come across before. I certainly never had until a few years ago. It’s from a French philosopher and anthropologist, so buckle up. René Girard was a French intellectual who gradually formed the idea of mimetic theory and the scapegoat mechanism. It’s an anthropological approach to the violence of humankind which he applies to the death and resurrection of Jesus. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

Both of these concepts are quite complicated and complex, so I will just give a brief overview but provide links for further reading. Humans learn through mimicking other humans. Babies learn by watching, listening, and taking in the world around them. As we grow older, we learn by more observation. We copy the community around us. We want to be like the other human beings around us. We learn to desire things, which is fine, but it can also lead to conflict and violence within a society. As this tension builds up, it has to be released somewhere. The scapegoat mechanism involves the process of blaming an individual or a certain group of people for the ills of a community, society, country, etc. Girard proposed that every culture in human history has developed a scapegoat mechanism of some kind to let off this steam, vent this frustration, and avoid more widespread, uncontrolled violence.

The term comes from the Old Testament where the Jewish priests would symbolically transfer the sins of the people onto a goat, and then that goat would be driven out into the desert. Presumably to die in the wilderness. Their violence was transplanted from their hearts onto this innocent animal who was then subjected to violence in their place. In the Hebrew tradition, only an animal was affected. But throughout history, humans have been as well. Animal sacrifice is an element of the scapegoat mechanism, but so was human sacrifice in the cultures that practiced it. The example that most readily comes to mind is probably the Holocaust in Nazi Germany. The country had been decimated by World War I and was subsequently plunged into poverty and societal shame. They had to blame someone for the situation they found themselves in as a country. But they didn’t blame themselves or the Treaty of Versailles which had (wrongly) laid most of the blame for the war at the feet of Germany. No, they needed a scapegoat. And they found one. Several, actually. People who were not “pure” enough in the eyes of Nazi ideology were targeted. Having been persecuted as “Christ-killers” for centuries throughout Europe, Jews were the dominant target. And there were just so many European Jews in countries like Germany, Austria, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and so on. But the Nazis also scapegoated other groups: Roma (gypsies), the LGBTQIA+ community (especially trans men and women), Marxists, communists, socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, academics, and intellectuals. All of these groups were blamed for the country’s ills following World War I even though they were not responsible in any way.

The Holocaust is just the largest, clearest example within living memory. It ended less than 80 years ago. People can still remember it, and there are still survivors living amongst us. But the scapegoat mechanism has happened all throughout history and all over the world. It is not distinct to the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism and Christianity. It’s a human condition of society in general. Girard posited that scapegoating enables the survival of society. It is some kind of necessary violence intended to safeguard against an out-of-control chaotic violence. He and others who have expanded upon this idea also theorized that the violent God depicted in the Old Testament is also merely an image of the scapegoat mechanism. Humanity demands violence, not God. We projected our own internalized violence onto God and the claimed that They wanted that violence. This can be seen in the biblical accounts of the conquest of Canaan (Palestine) by the Israelites. It can be seen in historical events like the various Crusades in the Holy Land and the religious wars in Europe during the Middle Ages and Protestant Reformation. God allowed Themself to be scapegoated by humanity. They didn’t demand violence of us, and the sacrifices of the Old Testament were only meant to appease humanity’s guilty conscience. Not God’s anger.

This projected violence carries over into Christian atonement theories like the widespread PSA (penal substitutionary atonement) that is so dominant in Western Christianity, and White evangelicalism in particular. In this theory, God is just and must punish sin, but He doesn’t want to condemn His children to eternal damnation. So He sends Jesus to be crucified and satisfy His bloodlust. It is a very pagan (i.e. non- Christian) idea and sets God up as a divine child abuser. But this was barely even a blip on the radar within any kind of Christianity until about 800 years ago. Less than half the timeline of Christianity! It’s a theory rooted in law, judgement, debt, and fines that developed alongside civil and criminal law (judicial vocabulary) and then later came to prominence with the spread of capitalism (economic vocabulary).

In contrast to PSA and other similar violence and retribution-based atonement theories, Girard proposes that God allowed Themself to be scapegoated, to have humanity’s bloodlust superimposed on Them. Later on, Jesus allowed himself to be scapegoated in order to unmask the entire process. The sin of the world (singular in the Gospels, not plural) is violence. The violence of the scapegoat mechanism. God and Jesus are both the victims of human violence. However, the defining difference comes with the Resurrection. Jesus somehow returns and begins to unravel the entire process of scapegoating. He is the innocent victim who resurrects, thus making people conscious of the process itself. When he says, “they don’t know what they’re doing” from the cross, he means it. The scapegoat mechanism is an unconscious process. People don’t know they’re taking part in it because it is hidden from their perception. Once it has been unmasked though, people are able to consciously choose to release the power that this violence holds over them. They can let it go.

In the story of the woman caught in adultery, Jesus consciously turns the tide of the scapegoat mechanism by telling the crowd that one person — someone who has never committed any sin — can throw the first stone. Someone has to break that dam, thus starting the process of collective punishment, by taking individual action. Once someone does that, the rest can then mimic them. The violence is then spread around to the group and the death of the scapegoat (the woman caught in adultery) will satiate their bloodlust. Jesus upends the process and saves the woman. He brings the crowd back from the unconsciousness of violence to the consciousness of non-violence and self-awareness. They must each act individually rather than as a group. A mob.

However, it is extremely difficult to go against the mob mentality. Think back to the footage of January 6th, 2021. Once the crowd had broken into the Capitol Building and was running amok through its halls, individuals couldn’t stop themselves from doing things that they would likely never have done on their own. They worked as a group, and very few stepped back to reconsider their choices. The die had been cast. No one in the crowd was able to break free on their own and put an end to the unfolding events. Similarly in The Passion of the Christ, only one person is able to break free and upend the scapegoat mechanism, although only momentarily. Saint Veronica is an extra-biblical tradition that comes from the ancient Stations of the Cross. She supposedly wiped the face of Jesus with her veil as he passed by on the Via Dolorosa, and his face was supernaturally imprinted on the cloth. As the scene is depicted in the film, Jesus has just fallen for maybe the tenth time or so, and she happens upon the scene holding a cup of water. Jesus is lying on the ground, the guards around him preoccupied with keeping the unruly crowd in check. It doesn’t appear that there are any followers of Jesus around, only enemies and those captivated by the bloodlust of a public execution. Veronica manages to walk through the crowd like an ethereal goddess wading through a sea of violence. She kneels down, removes her veil, and offers it to Jesus to wipe his face. She then tries to give him a drink of water, but the soldiers notice and kick the cup out of her hand. She is insulted and thrown violently back into the crowd. But for Jesus, he was given a brief moment of reprieve from the unrelenting torture. Apart from his own mother, Mary Magdalene, and John, no one in the crowd had attempted to show him really any human kindness up to this point. Veronica is the only one. Just as Jesus broke the scapegoat mechanism for the woman caught in adultery (thus saving her from death), Veronica broke the scapegoat mechanism (momentarily) for Jesus.

If Girard’s theories are accurate and Jesus did unmask this scapegoating trait of humanity, it still doesn’t mean it’s completely gone from human culture and society. We simply have the tools to become conscious of it. It hasn’t disappeared though. In fact, it could be argued that the scapegoat mechanism is playing out right now in Gaza. It has been playing out for the past 75+ years in all of Palestine. Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews were the targets of European anti-Semitism for centuries, finally culminating in the Holocaust. But Palestinians have been the scapegoats for European anti-Semitism and Zionism since at least 1948. Genocide and ethnic cleansing are the fruits of blaming the victim for their own demise. If you pay attention to what the 24-hour news networks in the West are busy not reporting, then you can see it much more clearly. Independent media, non-Western media, Palestinian journalists on the ground in Gaza (more than 130 of whom have been targeted by Israel), and unedited footage coming out of Gaza on platforms like TikTok and Instagram show a much different story than CNN, MSNBC, BBC, or The New York Times show. And when it comes to official government spokespeople, don’t listen to what they are saying in English when Western cameras are present. Listen to what they are saying in Hebrew when speaking before the Knesset or being interviewed by Israeli media. These are their real views, and they are genocidal.

For more than 75 years, we in the West have hidden our own violence (anti-Semitism) as well as Israel’s violence (Zionism) behind the violence of Hamas and other similar organizations. Whether you think of Hamas et al. as terrorists or freedom fighters, it cannot be argued that they don’t use violence. They do. But from the Western perspective, their violence is unacceptable while that of the West and Israel are justified. However, all violence is unacceptable. We incarcerate or execute the individual murderer while celebrating the advances of weapons manufacturers and the murder of at least 40,000 Palestinians (at least 15,000 of them children) at the hands of the Israeli state. They are the same crimes; the only difference is the scale.

Apart from the genocide unfolding before us on social media, there is also the rampant sexual abuse within Israeli prisons and on display as the IDF ransacks Palestinian homes in Gaza. Israeli soldiers just keep filming themselves committing war crimes and then uploading those videos to TikTok for the entire world to see. Mocking Palestinian women as they rifle through the private possessions they were forced to leave behind. These IDF soldiers display unknown women’s bras, underwear, and lingerie like trophies. This is sexual humiliation of not just individual women but an entire ethnic group. There have been multiple instances of the IDF forcing groups of men and boys to strip down to their underwear and parade nearly naked through the streets. This is sexual abuse. The UN has documented the widespread physical abuse and sexual assault of Palestinians (including children and teens) held in Israeli prisons, often without any charges whatsoever. This is sexual violence.

Just as was documented during the Latin American dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s, military occupation and systemic oppression are commonly linked to sexual abuse, assault, and torture. Or think back to the US military’s treatment of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. The violence and torture were highly sexualized, demeaning, and dehumanizing. What’s the most common joke in the US about men’s prisons? Becoming someone’s “prison wife” and warnings to not “drop the soap.” Yeah, rape jokes. Incarceration, oppression, and occupation frequently go hand in hand with sexual abuse, assault, and torture. It is thus not surprising that the IDF is using similar tactics of sexual violence. What is shocking is that they’re just posting videos online for anyone with an Internet connection to see. The videos themselves are almost like trophies. It came out just a week or two ago that Israel had actually tortured UN workers into giving false confessions about UNRWA staff having participated in the October 7th attacks alongside Hamas. Based on what I’ve read in The Shock Doctrine and the David Tombs study, I would not be surprised to find out that sexual violence was included in that torture. The question is, how do we put an end to this genocide? This oppression, dehumanization, humiliation, and torture of an entire nation? How do we upend the scapegoat mechanism currently unfolding in Gaza? How do we make sure it never happens again?

At the very end of The Passion of the Christ, his remaining followers and a couple of Roman soldiers lower Jesus’ dead body to the ground where he is cradled in his mother’s arms. In most films and series, the actors do not engage the audience. They don’t make eye contact with the camera. They don’t speak directly to you, the viewer. This film’s version of the Pietà does. As Mother Mary holds her son’s dead body, her hand lying open above his stilled heart, she slowly looks up and makes eye contact with the audience. The viewer. Us. Almost pleading with us not to do this again. To anyone. Upend the process of scapegoating, please. Just a few moments later, we see the stone rolling back from the tomb’s entrance and the burial shroud sort of deflating like a cocoon. Jesus has been transformed from a lowly caterpillar into a majestic butterfly. The pain, torture, humiliation, and whatever else have been transformed into something far better. The scapegoat mechanism has been upended, cancelled, unmasked. It’s an invitation for us to do the same.